Make Finance & Accounting Your Business Growth Engine

INsourced accounting & finance experts to help solve your most critical challenges quickly.

TRUSTED BY INDUSTRY LEADERS

What We Do

Solving Your Critical Finance & Accounting Challenges

8020 is INsourced corporate finance & accounting consulting to expertly solve critical enterprise finance challenges. Let us help you focus on the critical 20% of efforts that drive 80% of your financial results.

Our team of 100+ highly experienced financial experts become a part of your team to help elevate your operation & overachieve your goals. We strategically identify the critical few initiatives that generate the most significant business value and then embed a curated, highly specialized experts onto your team to solve your specific critical challenges quickly, so that you can get back to growth.

Avg. Consultant Experience

Full-Time Consultants

Years in Business

Projects Completed

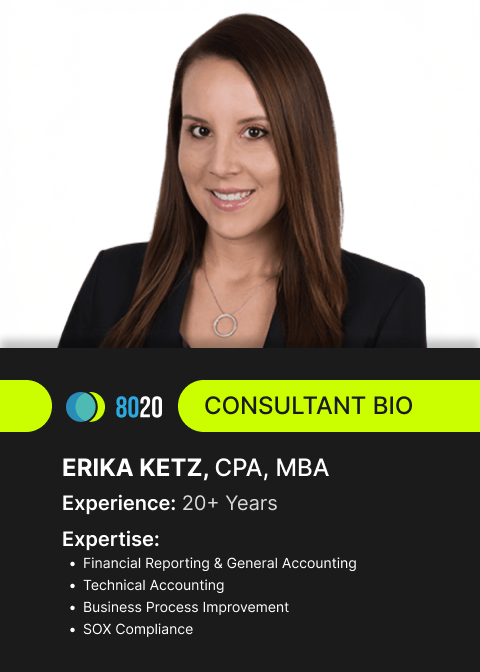

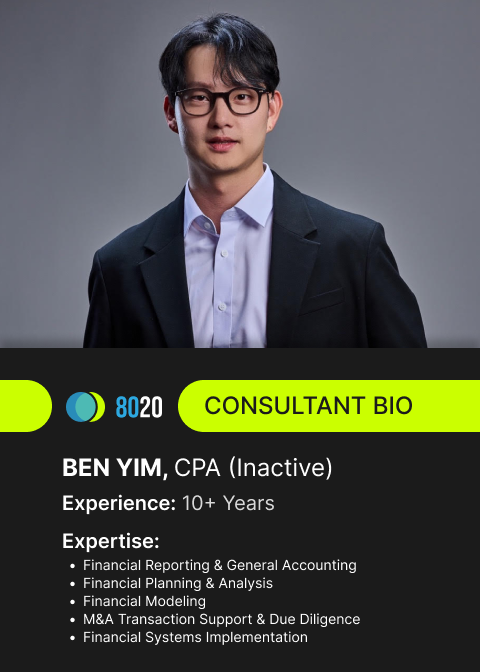

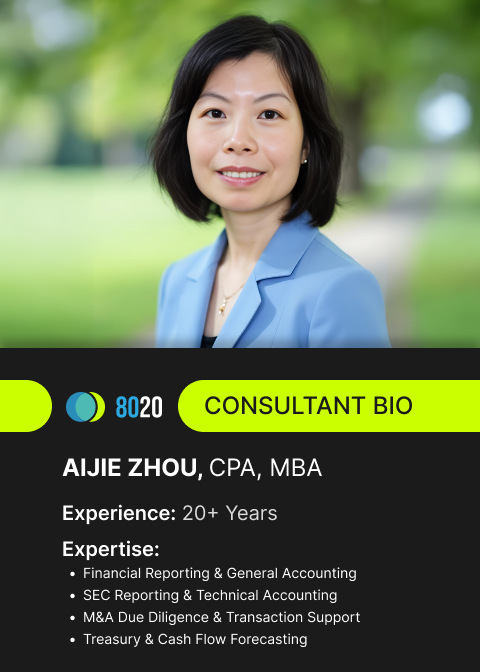

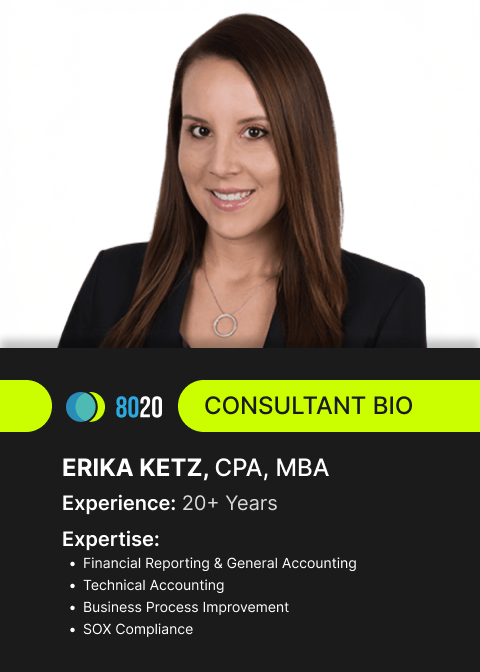

Meet Some of Our Experts

All the right skills, real-world experience, & high EQ leadership to ensure your success.

Featured 8020 Offerings

Take a closer look at three of our most requested offerings.

-

Interim Financial Management

Navigate leadership changes effortlessly with expert interim management services. Get immediate support, realign roles, & optimize performance during critical transitions.

-

Financial Planning & Analysis

Elevate your decision-making by adding expert forecasting, strategic planning, & detailed holistic analysis that allows you to optimize teams & your financial performance.

-

Financial Project Execution

Deliver successful project outcomes with ease with expert consultants that help you manage all critical financial elements to ensure your projects are completed efficiently & accurately.

The Industry's Only INsourced Finance & Accounting Services

From interim leadership, to holistic FP&A support, to IPO and M&A services, our consultants add the exact experience you need.

Financial Reporting & Accounting

Expert reporting & audit services for all industries — supporting initiatives like ASC 606, IPO readiness, audit preparation, and process improvement to elevate your team & your financial operations.

Financial Systems

Maximize the power of your tech stack with our systems review & optimization. Expertise in system selection, implementation, and post-go-live support to enhance team efficiency and overachieve on your tech goals.

Financial Project Management

Over deliver on this year's business objectives by adding expert financial project management resources. Get a fresh project outlook while minimizing team burden and ensuring successful project outcomes.

Mergers & Acquisition Due Diligence Support

With dozens of successful deals under our belt, our M&A experts support your buy/sell transactions with precise analysis, integration clairvoyance, and strategic insights to maximize deal value and streamline the processes.

Financial Turnaround & Restructuring

Navigate financial turmoil (and opportunity!) with experts who've done exactly this successfully many times. Leverage strategic guidance, crisis management, and operational restructuring to restore stability and drive recovery quickly.

IPO Readiness & Public Company Support

With an average 20+ years of experience to help you navigate the complexities of going public our operators ensure your success by leading your readiness, all filings, and post-IPO services tailored to your specific needs.

Financial Technology Integration

Your finance & accounting tech stack has wide-reaching impact on your entire business, not just your finances. Get expert support to ensure that you have the right tools & services to drive your financial success.

Private Equity Finance & Accounting Needs

Our team leverages extensive PE experience to maximize deal value, build scalable operations, and drive EBITDA growth while delivering measurable results throughout the investment lifecycle.

"8020 was crucial for RealD in developing a financial model for technology IP monetization and guiding our ERP selection process. Their work is thorough, executive-ready, and their team effectively implements recommendations."

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | 5.0

Jeff Spain

CFO, ReaID

"8020 was key in overhauling our budgeting process at 72andSunny and provided crucial support for system implementations like Workday and Oracle."

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | 5.0

Jordan Toplitsky

CFO, 72andSunny

"The team at 8020 have supported me across three companies, including managing our NetSuite implementation at Edgecast, integrating billing systems post-acquisition by Verizon, and overseeing our HQ relocation."

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | 5.0

John Powers

CFO, Tithe.ly

"8020's consultant brought a proactive approach to every challenge, consistently exceeding expectations while strengthening our team dynamic. I highly recommend 8020 for their skilled professionals who deliver immediate value and elevate any team."

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | 5.0

Lindsay Terifay

VP, Controller - Fandango & NBC Sports

Every financial project or leadership transition is an opportunity to re-evaluate, realign, & optimize your stack

We diagnose and deploy an expert with deep technical expertise and hands-on operational experience to solve your specific challenge. All of our consultants have successfully executed this work before and partner with you to help drive the outcomes you need.

Energize Your Projects While Decreasing

Team Burnout & Turnover

Get big operational & moral boosts with the perfect addition of skill & expertise while taking the pressure off your team so they can continue focusing on the important day-to-day.

Solve Your Most Critical Challenges With The Industry’s Most Skilled Consultants

Get rapid diagnosis & deployment of the right consultant with the exact deep experience you need to get your projects done right on time, every time.

Save Money & Optimize Your

Team So You Can Focus On Growth

Instantly take the pressure off so you can get back to your most important, strategic projects, help upskill the team, & save on total cost of project ownership.

Improve Your Infrastructure, Increase Team Efficiency, & Uplevel Your Stack

Fill gaps while increasing your team's performance using finance ops & tech experts who bring 20+ years average experience to help you modernize & optimize your stack.

Avoid Costly Fines & Sanctions

& Always Stay Compliant

Add compliance & regulation experts to ensure that you’re checking all the boxes necessary to stay compliant, eliminate fees & penalties, and operate as effectively as possible.

Our Promise

The 8020 Commitment

The 8020 commitment ensures you always get the right consultant to successfully complete your project as expected the first time or we'll make it right.

Every 8020 consultant brings the support of our entire 100+ team to your project.

Have a critical or immediate financial challenge?

Connect with one of our 100+ consultants that have an average of 20 years' experience solving the exact challenges you're facing.